The turn of the 20th century brought a major breakthrough in all existing art forms. The phenomenon, which we call “director’s theatre”, transformed all the elements of theatre, all its components – up to the cloakroom at Stanislavsky’s theatre. Performing arts in general started playing a much more important role than in the previous centuries. Not surprisingly, this process did not exclude puppet theatre. Thanks to the complete rethinking of the actor’s place on stage, at a certain moment the puppet reached the same level as the live actor and even started being perceived as the ideal actor.

Puppet theatre of the 19th century openly craved complete identification with “human” theatre – in plays, genres, outward appearance, and plasticity. Furthermore, having achieved maximal similarity, it started moving, like other art forms, in a different direction – towards the development of uniqueness and personal touch.

Parallel to that, drama theatre discovered in the puppet something that it could not find in the 19th century actor. Perhaps the main principles were formulated by Gordon Craig in his numerous texts about marionettes and über-marionettes. In 1907, in his essay The Actor and the Über-marionette, Craig wrote that the entire European culture was directed towards the depiction of emotions, towards presenting ourselves through the art, whereas genuine art should not express personality – it should express spirit and truth. However, the actor is only capable of reflecting the facts of reality. “So it is not lightly and flippantly that I speak of Puppets and their power to retain the beautiful and remote expressions in form and face even when subjected to a patter of praise, a torrent of applause.”

An audience member, living at the same time as Craig, laughed at the marionette, because it expressed the shortcomings which reflected those of his own. “… but you would not have laughed had you seen him in his prime, in that age when he was called upon to be the symbol of man in the great ceremony, and, stepping forward, was the beautiful figure of our heart’s delight.”

Craig referred to the historians of his time who suggested that ancient theatre performances started with puppets, not live actors (for example, in Ancient Egypt). The new actor – the über-marionette – is as impersonal and super-personal as the marionette.

Thus the situation in theatre turned upside down. However, even before that – in the aesthetics of naturalism – a theatre trend, which was grotesque in its form and melodramatic in its spirit, had been gradually formed: grand-guignol, the sheer name of which refers to the 19th century puppet character from Lyon who was mischievous and ruthless. In the theatre of Grand-Guignol in Paris (later this trend spread all over Europe, including St. Petersburg), the naturalistic depiction of mundane cruelties was brought to such level of exaggeration that actors who performed there were no longer perceived as people made of flesh and blood. Lifelikeness turned into a caricature. At that point they started to construct a drama performance according to the laws of puppet performance.

And yet the biggest significance – as the ideal actor – was achieved by the marionette in symbolism. This happened before Craig – in the work of Maurice Maeterlinck. In 1894 he published a collection of works titled The Marionette Plays, including Interior, Alladine and Palomides, The Death of Tintagiles. It is absolutely obvious that the aesthetics of the plays did not imply any kind of puppet specifics. The symbolists perceived the marionette as the only possible performer of drama, in which all the human feelings and passions withered away, making room for the sense of hidden truth and cosmic harmony.

The common idea about the marionette in symbolism as an allegory of helplessness and submissiveness: “The dependence of man on the law of existence is expressed here to its ultimate degree: man is no more than a marionette whose every movement is determined by the superior will” , – does not reflect the principal meaning, assigned to the marionette. This is the possibility to convey the proximity to “the tragic ordinariness” in a more objective way than by means of a human body, and to symbolically signify this inexpressible entity.

It was from the aesthetics of symbolism that the new forms of puppet theatre grew. One of the most important works, a real breakthrough for theatre – the trilogy about father Ubu by Alfred Jarry which began in 1896 with the play King Ubu at the Théâtre de l’Œuvre – in the early 20th century turned into an independent play, Ubu at the Vantage Point (Ubu on the Hill), specially intended for puppet theatre. Jarry reworked the story according to the logic of interaction between puppet characters, but kept the uniqueness and actuality of the characters in the drama version.

For many years Craig wrote short multi-genre plays for puppet theatre. His intention was to create 365 plays – for every day of the year; he ended up creating several dozens. In the vigorously developing plots there were both characters-masks and new contemporary characters. Using puppet form to express the principal universal features of the characters, Craig did not aspire to touch upon ontological reality. Here, in the laconic form, the aesthetics of grotesque and irony was embodied.

The theatre of modern inherited a lot from symbolism. The puppet became the character of synthetic theatre. This was most vividly realized in Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka, choreographed by Michel Fokine at the Ballets Russes in Paris. Characters of the puppet farce came to life through exaggerated human feelings. The images preserved the outward characteristics of puppets, but were interwoven into the general pictorial and movement pattern of modern.

In The Fairground Booth by Alexander Blok–Vsevolod Meyerhold commedia dell’arte masks came to life. The symbolist concept of the play and its production used the devices of modern in an organic way: an endless reflection of theatre in theatre, theatralization of reality, and destruction of stage conventions.

The futurists suggested a totally different way of using puppets and puppet theatre traditions. The Italian futurist artists wrote manifestos and produced plays in which “artificial living creatures” (Fortunato Depero) acted – theatre automatons, machine men. The project – conceived, but not realized in 1917 – was titled Automatic Murders and Suicides. Extreme and cruel accidents, happening to the characters – mechanisms looking like real people – made all kinds of visual transformations possible. The costumes, designed by Giacomo Balla, maximally limited actors’ movements and turned the image into the live puppet. In certain productions Balla managed to remove from stage not only the actor, but even the human-like mechanism. Pure theatrical action evolved with the participation of structures and abstract objects.

The puppet acquired a special meaning in the theatre of Dadaism. In fact, the expression “the theatre of Dadaism” included every form of artistic influence. In conjunction with Dadaism it is possible to speak about a whimsical synthesis of the most contrasted forms. The Dadaist provocations became the creative objectives for the artists of the entire 20th century. It is in Dadaism that the puppet and the performer became totally equal for the first time; the division between the two was deliberately rejected.

February 5, 1916 marked the beginning of daily performances of the Zurich Cabaret Voltaire, founded by Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Hans Arp, and Richard Huelsenbeck. Emmy Hennings was a well-known Munich dancer, successfully performing poetry, songs, and dances in cabaret programs. Having spent half a year in the German prison for helping emigrants at the beginning of the war, she moved to Switzerland. During the Zurich period Hennings performed in Dadaist programs using the glove puppets she made herself.

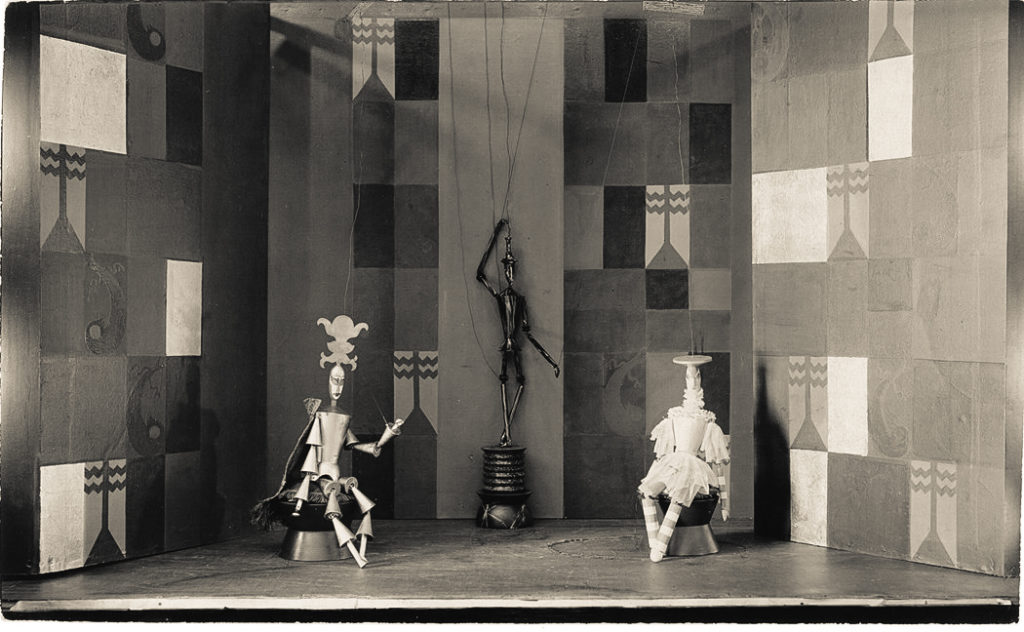

Before the war, in Munich, choreographer Rudolph von Laban created a dance school, where one of the dancers was Sophie Taeuber. During the war both of them found themselves in Zurich. The dance company of Rudolph von Laban, who had by 1920 formulated a new choreographic system of “expressive dance”, joined the Dadaist programs. Sophie Taeuber directed The Song of the Flying Fish and Seahorses with Laban’s dancers at the Cabaret Voltaire. However, gradually Taeuber started devoting more attention to the creation of theatre puppets, which embodied not specific characters, but generalized emotional states, vivid symbols. When in 1918 the Cabaret Voltaire closed and its founders went in different directions to various corners of Europe, Sophie Taeuber kept organizing all sorts of events with the marionettes she had made herself. In 1918 Taeuber directed The Stag King. She created marionettes, using cylinders, cones, balls, and sticks, made to look like human bodies. Taeuber’s images demonstrated the mechanic structure of the distorted body. During the same years Taeuber designed costumes for actors which made them look like puppets.

Besides that, one of the highlights of the Cabaret Voltaire was the creation of stylized African masks by Marcel Janco. The costumes, specially designed for this occasion, became the extension of the masks. Putting on these masks-costumes, the participants of the Cabaret Voltaire transformed. According to the memoirs of the participants, their movements, their voices changed. Here actors were not needed – creative transformation could happen to anyone. The man turned into the marionette as Craig understood it.

Theatralization of life and synthesis of the arts were the fundamental ideas of Dadaism. The theatre puppet played an important role in this context, but it was interwoven into the general creative life movement and was not classified as an independent form.

In November 1919 in Berlin, the Sound and Smoke cabaret, created before the war by Max Reinhardt at the Deutsches Theatre, resumed its activities. Now the cabaret programs were by and large determined by the Dadaists. In April 1920 the third edition of Der Dada magazine was published, including the materials, represented at the cabaret. On the first page, next to the poem Dada Schalmei by Richard Huelsenbeck (editor of the Berlin Dada Almanach), there was a picture of the puppet, made by Georg Gross and John Heartfield for the production Just Classics! The Oresteia with a Happy End. That was a parody, written by Walter Mehring in response to Aeschylus’s Oresteia, directed by Reinhardt at the Deutsches Theatre. The puppet representing a burgher in pince-nez with a tie on his thick neck and a cap in his hand, brought to life the character of Gross’s acute political graphics. In this model of a production, the contemporary man was likened to the grotesque puppet. This is not so much a Dadaist theatre concept as it is the precursor of Epic theatre. In 1928, in Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk directed by Erwin Piscator, the only live character was Švejk, performed by Max Pallenberg, and the characters-“marionettes” arrived at the stage on the moving-belt conveyor.

An absolutely unique place in the 20th century experimental theatre is occupied by the Laboratory Art et Action, created in 1919 in Paris by actress Louise Lara and architect Édouard Autant. With this group, the history of laboratory theatres started. Here puppet theatre was of paramount significance. Each of the theatre’s infrequent premieres became the discovery of new artistic principles, the embodiment of theatre synthesis.

In 1922, Romain Rolland’s play Liluli was staged in the aesthetics of shadow theatre. Its characters-silhouettes developed in an ironic way the symbolist principle of equating the ordinary world with the two-dimensional image. One of the most significant premieres of the Laboratory was The Wedding by Stanisław Wyspiański (1923) in the aesthetics of Polish szopka. The performers imitated puppet movements, their faces were covered with masks, at the ending of the show the actors were replaced by mannequins. The Pantoum of Pantoums (1925) was based on the texts of Indonesian four-liners – pantoums. In this production flat puppets with pivots were used, and the action itself was governed by the laws of wayang kulit.

Various models of the interaction between the puppet and other types of theatre actively developed in the 1890–1920s, when several trends, directed towards the total theatre and universal influence on the audience, appeared simultaneously. New perceptions about the actors’ existence and the subject of the performance appeared. In the middle of the 1930s the era of synthesis ended. The period of thorough development of the most sustainable forms inside different branches of theatre started.